System Security Concepts: The Foundation of Security Governance

Article 1 of 7 in the System Security Concepts series

The Documentation Gap

Most organisations struggle with a fundamental question: “How secure is System X, and who’s responsible if something goes wrong?”

The struggle isn’t technical. Firewalls work, encryption functions, access controls enforce policy. The problem is communication and accountability.

Walk into most organisations and you’ll find fragmented security documentation—if it exists at all. Risk assessments live in spreadsheets. Architecture decisions sit in email threads. Compliance evidence gets assembled reactively when auditors arrive. Technical controls are documented in wikis that nobody maintains.

Ask different stakeholders about the same system’s security posture and you’ll get different answers. The CISO wants to know the risk exposure. The business owner wants to know if they can launch. The security team wants to know what controls to implement. The technical architect wants to know how security requirements affect design.

These aren’t competing questions—they’re different views of the same reality. Yet most organisations answer them separately, creating misalignment, delays, and expensive last-minute discoveries.

The solution isn’t more documentation. It’s the right documentation: a System Security Concept.

What Is a System Security Concept?

A System Security Concept is a structured document that describes how a specific system or application achieves its required security posture. It connects business requirements to technical controls, documents threats and risks, defines ownership, and provides the evidence basis for security decisions.

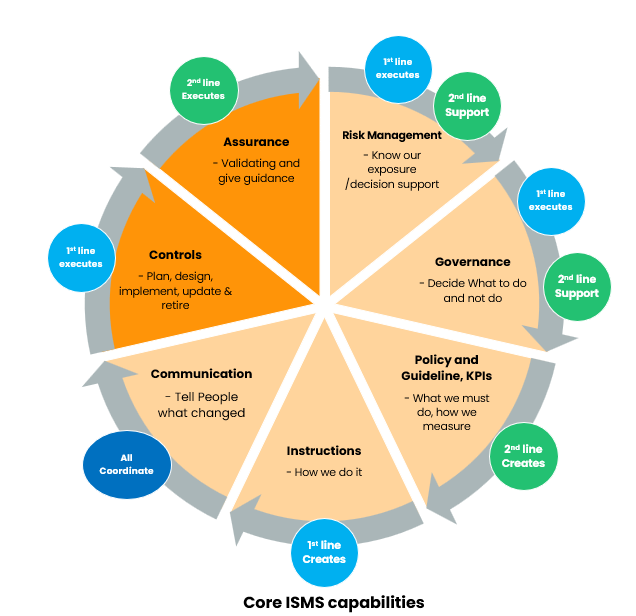

Within an Information Security Management System (ISMS), the security concept serves dual purposes:

As a control: It ensures security is designed into systems rather than bolted on afterwards. The concept documents how the organisation applies its security policies, standards, and controls to a specific system context.

As a support mechanism: It enables risk understanding across stakeholder groups, ensures required controls are implemented, and facilitates adaptation of enterprise security capabilities to specific system needs.

This positioning within ISMS frameworks like ISO 27001 elevates security concepts from “nice to have” documentation to essential governance instruments.

A well-constructed security concept answers four fundamental questions:

| Stakeholder | Primary Question | What the Concept Provides |

|---|---|---|

| CISO / Leadership | What is our risk exposure and who owns it? | Named accountability, residual risk documentation, portfolio-level visibility |

| Business Owner | Can we launch, and what constraints apply? | Go/no-go criteria, operational constraints, compliance status, risk acceptance framework |

| Security Team | What controls are required and why? | Control requirements, implementation guidance, review criteria, reusable patterns |

| Technical Architect | How do security requirements shape design? | Design constraints, integration requirements, change triggers, capability dependencies |

When these questions get answered in isolation, you get misalignment. When they’re answered in one coherent document with clear ownership, you get both speed and assurance.

The Maturity Progression: Common Mistakes

Through implementing ISMS programmes and reviewing security architectures across different organisations, a clear maturity pattern emerges:

Level 0: No Documentation The least mature organisations have no systematic security documentation for individual systems. Security decisions are made reactively, tribal knowledge dominates, and every security review starts from scratch. When incidents occur, there’s no baseline to assess what went wrong or who was accountable for what decision.

Level 1: Business Process Documentation Slightly more mature organisations document systems, but the focus is business processes and functional requirements. Security appears as a checklist item, if at all. These documents answer “what does the system do?” but not “how is it protected?” or “what are the security assumptions?”

Level 2: Security Documentation Without Integration More mature organisations create security-specific documentation. Threat models exist. Risk assessments are conducted. Control frameworks are documented. This represents significant progress, yet a critical gap remains: enterprise security capability integration.

The documentation describes what security controls the system should have, but not how it integrates with enterprise capabilities like IAM/SSO, SIEM, vulnerability management, incident response, DLP, and security testing pipelines.

This gap creates three problems. Security capabilities are duplicated rather than reused. Integration failures surface late in implementation. The enterprise security architecture remains invisible—a collection of disconnected system-level controls rather than a coherent capability model.

Level 3: Integrated Security Concepts (Target State) Leading organisations document security at the system level whilst explicitly mapping to enterprise capabilities. Their security concepts show not just “what controls exist” but “how this system leverages enterprise security infrastructure” and “where gaps exist that require system-specific controls.”

This integration enables portfolio-level thinking. Stack all security concepts together and you gain visibility into your actual enterprise security architecture—which capabilities are mature and reused, which are immature and duplicated, and where investment should flow.

The Ownership Question: A Pragmatic Answer

One question consistently generates debate: who should own the security concept document?

Some organisations assign ownership to security teams. Others create a separate “security architect” role. Some leave it ambiguous, hoping accountability emerges organically. None of these approaches work reliably.

Someone must own the security concept. From practical experience, the IT or system architect is the most effective owner. Not on ideological grounds, but for operational reasons:

System change visibility: The system architect tracks changes to functionality, integrations, and infrastructure. They’re positioned to recognise when changes have security implications and trigger security concept updates. If security owns the concept, they learn about changes late or not at all.

Trade-off authority: Security decisions involve trade-offs with performance, cost, usability, and functionality. The person accountable for the whole system must make these trade-offs coherently. Splitting system and security ownership creates handoff friction and diffused accountability.

Lifecycle continuity: Systems evolve over years. The architect who designs the system and owns its evolution must maintain the security concept as a living document. Security teams cannot own concepts for every system in the portfolio—they don’t scale.

Threat landscape adaptation: New vulnerabilities emerge. Attack patterns evolve. The security concept must adapt. The architect closest to the system understands which new threats are relevant and which aren’t—they have context that enables proportionate response.

This doesn’t mean architects work in isolation. Security teams provide threat intelligence, control expertise, review and challenge, and escalation paths for novel risks. The architect is accountable; the security team is a partner. This is consultation, not abdication.

Organisations that split ownership between “business architecture” and “security architecture” create coordination overhead without clear benefit. The most successful model: one architect, accountable for both functional and security aspects, partnered with security specialists who provide expertise without taking ownership.

The Velocity Myth: Security as Enabler

“Security slows us down.”

This complaint appears so frequently it’s taken as truth. Business stakeholders cite security reviews as deployment bottlenecks. Development teams complain about late security requirements. Project managers add “security buffer” to timelines.

The diagnosis is wrong. Security doesn’t slow organisations down. Poor security processes do.

The traditional model positions security as a gatekeeper. Projects reach a gate, security identifies issues, projects return to fix them, the cycle repeats. This model creates three problems:

Late discovery: Security reviews happen after design decisions are made, often after significant implementation investment. Changing course is expensive and time-consuming.

Adversarial dynamics: Security is perceived as saying “no” rather than enabling “yes, if.” Trust erodes. Security gets involved later and later to avoid conflict, making the problem worse.

Non-scalable review: Every project gets reviewed from scratch because previous decisions aren’t captured in reusable form. The security team becomes a bottleneck because their expertise doesn’t compound.

Security concepts change this dynamic fundamentally.

When security concepts are created early (during design), requirements are front-loaded. The architect knows the security constraints before making irreversible technical decisions. Discovery happens when changes are cheap—on paper, not in production.

When security concepts capture patterns and reference architectures, similar systems can inherit approved approaches. The security review focuses on what’s different, not what’s standard. The security team reviews deltas, not entire systems. This scales.

When security concepts document business context and risk appetite, security teams can calibrate their advice appropriately. High-risk systems get rigorous review. Low-risk systems get lightweight review. Resources flow to actual risk, not perceived noise.

The result: organisations with mature security concept practices deploy faster than those without them. Security becomes visible early, requirements are clear, rework is minimised, and review cycles are shorter because less is novel.

Security slows you down when it’s a surprise. Security accelerates you when it’s a known constraint designed in from the start.

Early Planning: Security as Inception Activity

Security concepts should be created at project start, not mid-build. This principle applies regardless of project methodology—Agile, Waterfall, SAFe, DevOps, PRINCE2, or any other approach.

Why inception matters: security concepts identify work that must be planned and resourced. Threat modelling workshops don’t happen by accident—they require scheduled time and participant availability. Security architecture reviews need review capacity. Penetration testing requires testing windows and budget. Integration with enterprise capabilities creates dependencies on other teams.

Discovered late, these activities become schedule disruptions, budget surprises, and firefighting exercises. Planned early, they become normal project activities with appropriate resources and timing.

The security concept outputs inform project planning:

- Security activities identified: Threat modelling workshops, security design reviews, penetration testing, certification activities

- Resource needs identified: Security specialists, external testers, security tools, enterprise capability integration effort

- Timeline impacts identified: Review cycles at architecture gates, testing windows before launch, approval processes

- Dependencies identified: Enterprise IAM integration, SIEM onboarding, GRC platform setup, compliance assessments

Security work becomes visible in project plans rather than assumed to “just happen.” A threat model identifying need for penetration testing before go-live means the project plan includes a two-week testing window and budget for external testers. Discovering this requirement three weeks before planned launch creates chaos.

This isn’t about methodology prescription—different approaches integrate security planning differently. Agile teams might create security concepts during Sprint 0. Waterfall projects create them during requirements or design phases. DevOps teams create them before first pipeline deployment. The common thread: early, not late.

The result: security work gets the resources and timing it needs. Projects don’t discover security requirements after making irreversible architectural decisions. Security teams aren’t firefighting last-minute crises. Business owners understand security implications before committing to timelines.

Early security planning prevents late security chaos.

ISMS Integration: The Control and Support Mechanism

Within an ISMS framework, security concepts occupy a specific and valuable position. They are both a control in themselves and a support mechanism for other controls.

As a control, the security concept ensures:

- Security requirements are identified systematically for each system

- Threats are assessed in context, not generically

- Controls are selected with documented rationale, not arbitrarily

- Residual risks are identified, assessed, and accepted explicitly

- Accountability is clear and documented

This satisfies multiple ISO 27001 control objectives around risk assessment (Clause 6.1.2), security requirements of information systems (A.14.1), and supplier relationships (A.15) where relevant.

As a support mechanism, the security concept enables:

- Risk understanding across different stakeholder groups and expertise levels

- Translation between business impact language and technical control language

- Assurance that required controls are actually implemented, not just theoretically selected

- Adaptation of enterprise security capabilities to specific system contexts

- Evidence collection for audits and compliance assessments

The security concept sits at the intersection of policy, risk, controls, and implementation. It translates strategic security policy into tactical requirements for specific systems. It documents risk assessment outcomes and control selection rationale. It provides the evidence thread from business requirement to implemented control.

Without security concepts, ISMS programmes remain abstract—policies and procedures that struggle to connect to actual systems. With security concepts, the ISMS becomes concrete—you can trace from any system to the controls it implements, the risks it addresses, and the policies it satisfies.

The Communication Bridge

Security concepts are fundamentally communication instruments. They translate between different languages and perspectives:

Technical to Business: Instead of “we need TLS 1.3 with perfect forward secrecy,” the concept explains “customer data in transit is protected against interception by unauthorised parties, including sophisticated attackers.”

Business to Technical: Instead of “we need high security,” the concept translates to “confidential data classification requiring encryption, access logging, and quarterly access reviews.”

Strategic to Operational: Instead of “we comply with ISO 27001,” the concept shows specifically which controls from Annex A apply to this system and how they’re implemented.

Risk to Control: Instead of “there’s a risk of data breach,” the concept documents which specific threats could cause a breach, how likely they are given the system’s context, and which controls mitigate them.

This translation eliminates the most common source of friction in security programmes: stakeholders talking past each other because they’re using the same words to mean different things.

When security concepts are done well, they enable productive conversations:

- CISOs can aggregate portfolio risk from standardised system-level assessments

- Business owners can make informed risk acceptance decisions with clear understanding of implications

- Security teams can provide tailored guidance rather than generic requirements

- Architects can design with security as an integrated concern, not a bolt-on afterthought

- Auditors can efficiently assess control implementation without extensive documentation requests

The security concept becomes the single source of truth that everyone references, updates, and relies upon.

Making It Work: Core Requirements

Not all security concepts deliver value. Some become shelf-ware—created for compliance, filed, and forgotten. Others become maintenance burdens—so detailed they’re never updated, so generic they provide no guidance.

Effective security concepts share common characteristics:

Owned and Accountable: A named individual owns the document and is accountable for its accuracy and currency. This is typically the system architect, as discussed, but the critical requirement is clear ownership, not the specific role.

Appropriately Scoped: The concept covers one system or application, with clear boundaries. Concepts that try to cover entire technology stacks or business domains become unwieldy and hard to maintain.

Right-Sized: Documentation depth matches system risk and complexity. Business-critical systems with sensitive data warrant comprehensive concepts. Low-risk internal tools need lightweight concepts. One size does not fit all.

Integrated with Lifecycle: The concept is created during design, updated during implementation, maintained during operations, and consulted during changes. It’s not a point-in-time deliverable but a living document.

Linked to Enterprise: The concept explicitly references enterprise security capabilities and standards. It shows what’s reused and what’s system-specific. This enables both local understanding and portfolio-level visibility.

Evidence-Based: Claims about control implementation link to evidence—configuration screenshots, test results, access logs, monitoring dashboards. The concept isn’t aspirational; it reflects reality.

Stakeholder-Accessible: Different stakeholders should be able to find their answers quickly. Executives read the risk summary. Implementers consult the control specifications. Auditors review the compliance mapping. Structure supports multiple readers.

What This Series Covers

This article establishes the foundation: what security concepts are, why they matter, and how they function within security governance and ISMS frameworks.

The remaining articles in this series build on this foundation:

Article 2: Core Components examines what makes an effective security concept—system context, threat modelling, risk assessment, security requirements, and documentation structure.

Article 3: Control Selection and Security Frameworks addresses how to select controls systematically using frameworks like ISO 27001/27002, NIST CSF, IEC 62443, and CIS Controls, and how to build organisational control libraries.

Article 4: The Living Document addresses lifecycle integration and change management—how security concepts stay current as systems and threats evolve, and how they integrate with change advisory processes.

Article 5: Enterprise Security Capabilities tackles the integration challenge that most organisations miss—connecting system-level security concepts to enterprise capabilities and building visibility into the overall security architecture.

Article 6: Access Control and Data Protection provides detailed guidance on recurring security concept components—RBAC patterns, data classification, encryption standards, and monitoring requirements.

Article 7: Implementation Guide delivers practical templates, tooling recommendations, and a roadmap for organisations starting or improving their security concept practice.

Conclusion

Security concepts are not bureaucratic paperwork. They are governance instruments that connect business objectives to technical controls, establish accountability, accelerate deployments, and provide the evidence basis for security decisions.

Within ISMS frameworks, they function as both controls and support mechanisms—ensuring security is designed in and enabling risk understanding across stakeholder groups.

The organisations that implement security concepts effectively gain measurable advantages: faster deployments, clearer accountability, better risk visibility, and more efficient security operations. Those that treat them as compliance checkbox exercises wonder why security remains a bottleneck.

The difference lies in understanding what security concepts actually are—communication bridges, not compliance artifacts.

The next article examines the core components that make security concepts effective communication instruments and governance tools.

Next in series: Article 2 - Core Components: What Makes a Security Concept Effective

Article 1 of 7 | Ready for publication Target audience: CISOs, Security Directors, Enterprise Architects, Senior Security Specialists Word count: ~2,750